Monoclonal antibody

A monoclonal antibody (mAb, more rarely called moAb) is an antibody produced from a cell lineage made by cloning a unique white blood cell. All subsequent antibodies derived this way trace back to a unique parent cell.

Monoclonal antibodies can have monovalent affinity, binding only to the same epitope (the part of an antigen that is recognized by the antibody).[3] In contrast, polyclonal antibodies bind to multiple epitopes and are usually made by several different antibody-secreting plasma cell lineages. Bispecific monoclonal antibodies can also be engineered, by increasing the therapeutic targets of one monoclonal antibody to two epitopes.

It is possible to produce monoclonal antibodies that specifically bind to almost any suitable substance; they can then serve to detect or purify it. This capability has become an investigative tool in biochemistry, molecular biology, and medicine. Monoclonal antibodies are used in the diagnosis of illnesses such as cancer and infections[4] and are used therapeutically in the treatment of e.g. cancer and inflammatory diseases.

History

[edit]In the early 1900s, immunologist Paul Ehrlich proposed the idea of a Zauberkugel – "magic bullet", conceived of as a compound which selectively targeted a disease-causing organism, and could deliver a toxin for that organism. This underpinned the concept of monoclonal antibodies and monoclonal drug conjugates. Ehrlich and Élie Metchnikoff received the 1908 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for providing the theoretical basis for immunology.

By the 1970s, lymphocytes producing a single antibody were known, in the form of multiple myeloma – a cancer affecting B-cells. These abnormal antibodies or paraproteins were used to study the structure of antibodies, but it was not yet possible to produce identical antibodies specific to a given antigen.[5]: 324 In 1973, Jerrold Schwaber described the production of monoclonal antibodies using human–mouse hybrid cells.[6] This work remains widely cited among those using human-derived hybridomas.[7] In 1975, Georges Köhler and César Milstein succeeded in making fusions of myeloma cell lines with B cells to create hybridomas that could produce antibodies, specific to known antigens and that were immortalized.[8] They and Niels Kaj Jerne shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984 for the discovery.[8]

In 1988, Gregory Winter and his team pioneered the techniques to humanize monoclonal antibodies,[9] eliminating the reactions that many monoclonal antibodies caused in some patients. By the 1990s research was making progress in using monoclonal antibodies therapeutically, and in 2018, James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation, using monoclonal antibodies that prevent inhibitory linkages.[10]

The translational work needed to implement these ideas is credited to Lee Nadler. As explained in an NIH article, "He was the first to discover monoclonal antibodies directed against human B-cell–specific antigens and, in fact, all the known human B-cell–specific antigens were discovered in his laboratory. He is a true translational investigator, since he used these monoclonal antibodies to classify human B-cell leukemia and lymphomas as well as to create therapeutic agents for patients. . . More importantly, he was the first in the world to administer a monoclonal antibody to a human (a patient with B-cell lymphoma)."[11]

Production

[edit]

Hybridoma development

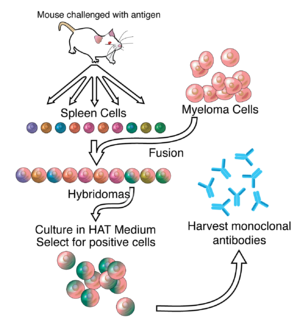

[edit]Much of the work behind production of monoclonal antibodies is rooted in the production of hybridomas, which involves identifying antigen-specific plasma/plasmablast cells that produce antibodies specific to an antigen of interest and fusing these cells with myeloma cells.[8] Rabbit B-cells can be used to form a rabbit hybridoma.[12][13] Polyethylene glycol is used to fuse adjacent plasma membranes,[14] but the success rate is low, so a selective medium in which only fused cells can grow is used. This is possible because myeloma cells have lost the ability to synthesize hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyl transferase (HGPRT), an enzyme necessary for the salvage synthesis of nucleic acids. The absence of HGPRT is not a problem for these cells unless the de novo purine synthesis pathway is also disrupted. Exposing cells to aminopterin (a folic acid analogue which inhibits dihydrofolate reductase) makes them unable to use the de novo pathway and become fully auxotrophic for nucleic acids, thus requiring supplementation to survive.

The selective culture medium is called HAT medium because it contains hypoxanthine, aminopterin and thymidine. This medium is selective for fused (hybridoma) cells. Unfused myeloma cells cannot grow because they lack HGPRT and thus cannot replicate their DNA. Unfused spleen cells cannot grow indefinitely because of their limited life span. Only fused hybrid cells referred to as hybridomas, are able to grow indefinitely in the medium because the spleen cell partner supplies HGPRT and the myeloma partner has traits that make it immortal (similar to a cancer cell).

This mixture of cells is then diluted and clones are grown from single parent cells on microtitre wells. The antibodies secreted by the different clones are then assayed for their ability to bind to the antigen (with a test such as ELISA or antigen microarray assay) or immuno-dot blot. The most productive and stable clone is then selected for future use.

The hybridomas can be grown indefinitely in a suitable cell culture medium. They can also be injected into mice (in the peritoneal cavity, surrounding the gut). There, they produce tumors secreting an antibody-rich fluid called ascites fluid.

The medium must be enriched during in vitro selection to further favour hybridoma growth. This can be achieved by the use of a layer of feeder fibrocyte cells or supplement medium such as briclone. Culture-media conditioned by macrophages can be used. Production in cell culture is usually preferred as the ascites technique is painful to the animal. Where alternate techniques exist, ascites is considered unethical.[15]

Novel mAb development technology

[edit]Several monoclonal antibody technologies have been developed recently,[16] such as phage display,[17] single B cell culture,[18] single cell amplification from various B cell populations[19][20][21][22][23] and single plasma cell interrogation technologies. Different from traditional hybridoma technology, the newer technologies use molecular biology techniques to amplify the heavy and light chains of the antibody genes by PCR and produce in either bacterial or mammalian systems with recombinant technology. One of the advantages of the new technologies is applicable to multiple animals, such as rabbit, llama, chicken and other common experimental animals in the laboratory.

Purification

[edit]After obtaining either a media sample of cultured hybridomas or a sample of ascites fluid, the desired antibodies must be extracted. Cell culture sample contaminants consist primarily of media components such as growth factors, hormones and transferrins. In contrast, the in vivo sample is likely to have host antibodies, proteases, nucleases, nucleic acids and viruses. In both cases, other secretions by the hybridomas such as cytokines may be present. There may also be bacterial contamination and, as a result, endotoxins that are secreted by the bacteria. Depending on the complexity of the media required in cell culture and thus the contaminants, one or the other method (in vivo or in vitro) may be preferable.

The sample is first conditioned, or prepared for purification. Cells, cell debris, lipids, and clotted material are first removed, typically by centrifugation followed by filtration with a 0.45 μm filter. These large particles can cause a phenomenon called membrane fouling in later purification steps. In addition, the concentration of product in the sample may not be sufficient, especially in cases where the desired antibody is produced by a low-secreting cell line. The sample is therefore concentrated by ultrafiltration or dialysis.

Most of the charged impurities are usually anions such as nucleic acids and endotoxins. These can be separated by ion exchange chromatography.[24] Either cation exchange chromatography is used at a low enough pH that the desired antibody binds to the column while anions flow through, or anion exchange chromatography is used at a high enough pH that the desired antibody flows through the column while anions bind to it. Various proteins can also be separated along with the anions based on their isoelectric point (pI). In proteins, the isoelectric point (pI) is defined as the pH at which a protein has no net charge. When the pH > pI, a protein has a net negative charge, and when the pH < pI, a protein has a net positive charge. For example, albumin has a pI of 4.8, which is significantly lower than that of most monoclonal antibodies, which have a pI of 6.1. Thus, at a pH between 4.8 and 6.1, the average charge of albumin molecules is likely to be more negative, while mAbs molecules are positively charged and hence it is possible to separate them. Transferrin, on the other hand, has a pI of 5.9, so it cannot be easily separated by this method. A difference in pI of at least 1 is necessary for a good separation.

Transferrin can instead be removed by size exclusion chromatography. This method is one of the more reliable chromatography techniques. Since we are dealing with proteins, properties such as charge and affinity are not consistent and vary with pH as molecules are protonated and deprotonated, while size stays relatively constant. Nonetheless, it has drawbacks such as low resolution, low capacity and low elution times.

A much quicker, single-step method of separation is protein A/G affinity chromatography. The antibody selectively binds to protein A/G, so a high level of purity (generally >80%) is obtained. The generally harsh conditions of this method may damage easily damaged antibodies. A low pH can break the bonds to remove the antibody from the column. In addition to possibly affecting the product, low pH can cause protein A/G itself to leak off the column and appear in the eluted sample. Gentle elution buffer systems that employ high salt concentrations are available to avoid exposing sensitive antibodies to low pH. Cost is also an important consideration with this method because immobilized protein A/G is a more expensive resin.

To achieve maximum purity in a single step, affinity purification can be performed, using the antigen to provide specificity for the antibody. In this method, the antigen used to generate the antibody is covalently attached to an agarose support. If the antigen is a peptide, it is commonly synthesized with a terminal cysteine, which allows selective attachment to a carrier protein, such as KLH during development and to support purification. The antibody-containing medium is then incubated with the immobilized antigen, either in batch or as the antibody is passed through a column, where it selectively binds and can be retained while impurities are washed away. An elution with a low pH buffer or a more gentle, high salt elution buffer is then used to recover purified antibody from the support.

Antibody heterogeneity

[edit]Product heterogeneity is common in monoclonal antibodies and other recombinant biological products and is typically introduced either upstream during expression or downstream during manufacturing.[25][26][27]

These variants are typically aggregates, deamidation products, glycosylation variants, oxidized amino acid side chains, as well as amino and carboxyl terminal amino acid additions.[28] These seemingly minute structural changes can affect preclinical stability and process optimization as well as therapeutic product potency, bioavailability and immunogenicity. The generally accepted purification method of process streams for monoclonal antibodies includes capture of the product target with protein A, elution, acidification to inactivate potential mammalian viruses, followed by ion chromatography, first with anion beads and then with cation beads.[citation needed]

Displacement chromatography has been used to identify and characterize these often unseen variants in quantities that are suitable for subsequent preclinical evaluation regimens such as animal pharmacokinetic studies.[29][30] Knowledge gained during the preclinical development phase is critical for enhanced product quality understanding and provides a basis for risk management and increased regulatory flexibility. The recent Food and Drug Administration's Quality by Design initiative attempts to provide guidance on development and to facilitate design of products and processes that maximizes efficacy and safety profile while enhancing product manufacturability.[31]

Recombinant

[edit]The production of recombinant monoclonal antibodies involves repertoire cloning, CRISPR/Cas9, or phage display/yeast display technologies.[32] Recombinant antibody engineering involves antibody production by the use of viruses or yeast, rather than mice. These techniques rely on rapid cloning of immunoglobulin gene segments to create libraries of antibodies with slightly different amino acid sequences from which antibodies with desired specificities can be selected.[33] The phage antibody libraries are a variant of phage antigen libraries.[34] These techniques can be used to enhance the specificity with which antibodies recognize antigens, their stability in various environmental conditions, their therapeutic efficacy and their detectability in diagnostic applications.[35] Fermentation chambers have been used for large scale antibody production.

Chimeric antibodies

[edit]While mouse and human antibodies are structurally similar, the differences between them were sufficient to invoke an immune response when murine monoclonal antibodies were injected into humans, resulting in their rapid removal from the blood, as well as systemic inflammatory effects and the production of human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA).

Recombinant DNA has been explored since the late 1980s to increase residence times. In one approach called "CDR grafting",[36] mouse DNA encoding the binding portion of a monoclonal antibody was merged with human antibody-producing DNA in living cells. The expression of this "chimeric" or "humanised" DNA through cell culture yielded part-mouse, part-human antibodies.[37][38]

Human antibodies

[edit]

Ever since the discovery that monoclonal antibodies could be generated, scientists have targeted the creation of fully human products to reduce the side effects of humanised or chimeric antibodies. Several successful approaches have been proposed: transgenic mice,[39] phage display[17] and single B cell cloning.[16]

Cost

[edit]Monoclonal antibodies are more expensive to manufacture than small molecules due to the complex processes involved and the general size of the molecules, all in addition to the enormous research and development costs involved in bringing a new chemical entity to patients. They are priced to enable manufacturers to recoup the typically large investment costs, and where there are no price controls, such as the United States, prices can be higher if they provide great value. Seven University of Pittsburgh researchers concluded, "The annual price of mAb therapies is about $100,000 higher in oncology and hematology than in other disease states", comparing them on a per patient basis, to those for cardiovascular or metabolic disorders, immunology, infectious diseases, allergy, and ophthalmology.[40]

Applications

[edit]Diagnostic tests

[edit]Once monoclonal antibodies for a given substance have been produced, they can be used to detect the presence of this substance. Proteins can be detected using the Western blot and immuno dot blot tests. In immunohistochemistry, monoclonal antibodies can be used to detect antigens in fixed tissue sections, and similarly, immunofluorescence can be used to detect a substance in either frozen tissue section or live cells.

Analytic and chemical uses

[edit]Antibodies can also be used to purify their target compounds from mixtures, using the method of immunoprecipitation.

Therapeutic uses

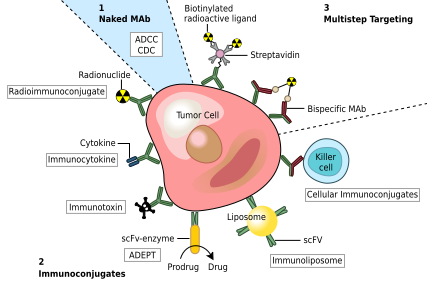

[edit]Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies act through multiple mechanisms, such as blocking of targeted molecule functions, inducing apoptosis in cells which express the target, or by modulating signalling pathways.[41][42][43]

Cancer treatment

[edit]One possible treatment for cancer involves monoclonal antibodies that bind only to cancer-cell-specific antigens and induce an immune response against the target cancer cell. Such mAbs can be modified for delivery of a toxin, radioisotope, cytokine or other active conjugate or to design bispecific antibodies that can bind with their Fab regions both to target antigen and to a conjugate or effector cell. Every intact antibody can bind to cell receptors or other proteins with its Fc region.

MAbs approved by the FDA for cancer include:[45]

Autoimmune diseases

[edit]Monoclonal antibodies used for autoimmune diseases include infliximab and adalimumab, which are effective in rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and ankylosing spondylitis by their ability to bind to and inhibit TNF-α.[46] Basiliximab and daclizumab inhibit IL-2 on activated T cells and thereby help prevent acute rejection of kidney transplants.[46] Omalizumab inhibits human immunoglobulin E (IgE) and is useful in treating moderate-to-severe allergic asthma.

Examples of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies

[edit]Monoclonal antibodies for research applications can be found directly from antibody suppliers, or through use of a specialist search engine like CiteAb. Below are examples of clinically important monoclonal antibodies.

| Main category | Type | Application | Mechanism/Target | Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti- inflammatory |

infliximab[46] | inhibits TNF-α | chimeric | |

| adalimumab | inhibits TNF-α | human | ||

| ustekinumab | blocks interleukin IL-12 and IL-23 | human | ||

| basiliximab[46] |

|

inhibits IL-2 on activated T cells | chimeric | |

| daclizumab[46] |

|

inhibits IL-2 on activated T cells | humanized | |

| omalizumab | inhibits human immunoglobulin E (IgE) | humanized | ||

| Anti-cancer | gemtuzumab[46] |

|

targets myeloid cell surface antigen CD33 on leukemia cells | humanized |

| alemtuzumab[46] | targets an antigen CD52 on T- and B-lymphocytes | humanized | ||

| rituximab[46] |

|

targets phosphoprotein CD20 on B lymphocytes | chimeric | |

| trastuzumab |

|

targets the HER2/neu (erbB2) receptor | humanized | |

| nimotuzumab |

|

EGFR inhibitor | humanized | |

| cetuximab |

|

EGFR inhibitor | chimeric | |

| panitumumab |

|

EGFR inhibitor | human | |

| bevacizumab & ranibizumab |

|

inhibits VEGF | humanized | |

| Anti-cancer and anti-viral | bavituximab[47] |

|

immunotherapy, targets phosphatidylserine[47] | chimeric |

| Anti-viral |

|

immunotherapy, targets spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 | human | |

| bamlanivimab/etesevimab[49] |

|

immunotherapy, targets spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 | human | |

| Sotrovimab[50] |

|

immunotherapy, targets spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 | human | |

| Other | palivizumab[46] |

|

inhibits an RSV fusion (F) protein | humanized |

| abciximab[46] |

|

inhibits the receptor GpIIb/IIIa on platelets | chimeric |

COVID-19

[edit]In 2020, the monoclonal antibody therapies bamlanivimab/etesevimab and casirivimab/imdevimab were given emergency use authorizations by the US Food and Drug Administration to reduce the number of hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and deaths because of COVID-19.[48][49] In September 2021, the Biden administration purchased US$2.9 billion worth of Regeneron monoclonal antibodies at $2,100 per dose to curb the shortage.[51]

As of December 2021, in vitro neutralization tests indicate monoclonal antibody therapies (with the exception of sotrovimab and tixagevimab/cilgavimab) were not likely to be active against the Omicron variant.[52]

Over 2021–22, two Cochrane reviews found insufficient evidence for using neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19 infections.[53][54] The reviews applied only to people who were unvaccinated against COVID‐19, and only to the COVID-19 variants existing during the studies, not to newer variants, such as Omicron.[54]

In March 2024, pemivibart, a monoclonal antibody drug, received an emergency use authorization from the US FDA for use as pre-exposure prophylaxis to protect certain moderately to severely immunocompromised individuals against COVID-19.[55][56]

Side effects

[edit]Several monoclonal antibodies, such as bevacizumab and cetuximab, can cause different kinds of side effects.[57] These side effects can be categorized into common and serious side effects.[58]

Some common side effects include:

Among the possible serious side effects are:[59]

- Anaphylaxis

- Bleeding

- Arterial and venous blood clots

- Autoimmune thyroiditis

- Hypothyroidism

- Hepatitis

- Heart failure

- Cancer

- Anemia

- Decrease in white blood cells

- Stomatitis

- Enterocolitis

- Gastrointestinal perforation

- Mucositis

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gelboin HV. "Cytochrome P450 Mediated Drug and Carcinogen Metabolism using Monoclonal Antibodies". home.ccr.cancer.gov. Archived from the original on 15 October 2004. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Gelboin HV, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ, Yang TJ (November 1999). "Inhibitory monoclonal antibodies to human cytochrome P450 enzymes: a new avenue for drug discovery". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 20 (11): 432–438. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01382-6. PMID 10542439.

- ^ Liu JK (11 September 2014). "The history of monoclonal antibody development – Progress, remaining challenges and future innovations". Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 3 (4): 113–116. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2014.09.001. ISSN 2049-0801. PMC 4284445. PMID 25568796.

- ^ Waldmann TA (June 1991). "Monoclonal antibodies in diagnosis and therapy". Science. 252 (5013): 1657–1662. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1657W. doi:10.1126/science.2047874. PMID 2047874. S2CID 19615695.

- ^ Tansey EM, Catterall PP (July 1994). "Monoclonal antibodies: a witness seminar in contemporary medical history". Medical History. 38 (3): 322–327. doi:10.1017/s0025727300036632. PMC 1036884. PMID 7934322.

- ^ Schwaber J, Cohen EP (August 1973). "Human x mouse somatic cell hybrid clone secreting immunoglobulins of both parental types". Nature. 244 (5416): 444–447. doi:10.1038/244444a0. PMID 4200460. S2CID 4171375.

- ^ Cambrosio A, Keating P (1992). "Between fact and technique: the beginnings of hybridoma technology". Journal of the History of Biology. 25 (2): 175–230. doi:10.1007/BF00162840. PMID 11623041. S2CID 45615711.

- ^ a b c Marks LV. "The Story of César Milstein and Monoclonal Antibodies". WhatisBiotechnology.org. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Riechmann L, Clark M, Waldmann H, Winter G (March 1988). "Reshaping human antibodies for therapy". Nature. 332 (6162): 323–327. Bibcode:1988Natur.332..323R. doi:10.1038/332323a0. PMID 3127726. S2CID 4335569.

- ^ Altmann DM (November 2018). "A Nobel Prize-worthy pursuit: cancer immunology and harnessing immunity to tumour neoantigens". Immunology. 155 (3): 283–284. doi:10.1111/imm.13008. PMC 6187215. PMID 30320408.

- ^ Nadler LM, Roberts WC (October 2007). "Lee Marshall Nadler, MD: a conversation with the editor". Proceedings. 20 (4). National Institutes of Health: 381–389. doi:10.1080/08998280.2007.11928327. PMC 2014809. PMID 17948113.

- ^ Spieker-Polet H, Sethupathi P, Yam PC, Knight KL (September 1995). "Rabbit monoclonal antibodies: generating a fusion partner to produce rabbit-rabbit hybridomas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (20): 9348–9352. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.9348S. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.20.9348. PMC 40982. PMID 7568130.

- ^ Zhang YF, Phung Y, Gao W, Kawa S, Hassan R, Pastan I, et al. (May 2015). "New high affinity monoclonal antibodies recognize non-overlapping epitopes on mesothelin for monitoring and treating mesothelioma". Scientific Reports. 5: 9928. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9928Z. doi:10.1038/srep09928. PMC 4440525. PMID 25996440.

- ^ Yang J, Shen MH (2006). "Polyethylene glycol-mediated cell fusion". Nuclear Reprogramming. Methods Mol Biol. Vol. 325. pp. 59–66. doi:10.1385/1-59745-005-7:59. ISBN 1-59745-005-7. PMID 16761719.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Methods of Producing Monoclonal Antibodies. "Recommendation 1: Executive Summary: Monoclonal Antibody Production". Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999. ISBN 978-0309075114

- ^ a b c Ho M (June 2018). "Inaugural Editorial: Searching for Magic Bullets". Antibody Therapeutics. 1 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1093/abt/tby001. PMC 6086361. PMID 30101214.

- ^ a b Ho M, Feng M, Fisher RJ, Rader C, Pastan I (May 2011). "A novel high-affinity human monoclonal antibody to mesothelin". International Journal of Cancer. 128 (9): 2020–2030. doi:10.1002/ijc.25557. PMC 2978266. PMID 20635390.

- ^ Seeber S, Ros F, Thorey I, Tiefenthaler G, Kaluza K, Lifke V, et al. (2014). "A robust high throughput platform to generate functional recombinant monoclonal antibodies using rabbit B cells from peripheral blood". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e86184. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...986184S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086184. PMC 3913575. PMID 24503933.

- ^ Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC (September 2003). "Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors". Science. 301 (5638): 1374–1377. Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1374W. doi:10.1126/science.1086907. PMID 12920303. S2CID 43459065.

- ^ Koelsch K, Zheng NY, Zhang Q, Duty A, Helms C, Mathias MD, et al. (June 2007). "Mature B cells class switched to IgD are autoreactive in healthy individuals". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (6): 1558–1565. doi:10.1172/JCI27628. PMC 1866247. PMID 17510706.

- ^ Smith K, Garman L, Wrammert J, Zheng NY, Capra JD, Ahmed R, et al. (1 January 2009). "Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen". Nature Protocols. 4 (3): 372–384. doi:10.1038/nprot.2009.3. PMC 2750034. PMID 19247287.

- ^ Duty JA, Szodoray P, Zheng NY, Koelsch KA, Zhang Q, Swiatkowski M, et al. (January 2009). "Functional anergy in a subpopulation of naive B cells from healthy humans that express autoreactive immunoglobulin receptors". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 206 (1): 139–151. doi:10.1084/jem.20080611. PMC 2626668. PMID 19103878.

- ^ Huang J, Doria-Rose NA, Longo NS, Laub L, Lin CL, Turk E, et al. (October 2013). "Isolation of human monoclonal antibodies from peripheral blood B cells". Nature Protocols. 8 (10): 1907–1915. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.117. PMC 4844175. PMID 24030440.

- ^ Vlasak J, Ionescu R (December 2008). "Heterogeneity of monoclonal antibodies revealed by charge-sensitive methods". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 9 (6): 468–481. doi:10.2174/138920108786786402. PMID 19075686.

- ^ Liu H, Nowak C, Shao M, Ponniah G, Neill A (September 2016). "Impact of cell culture on recombinant monoclonal antibody product heterogeneity". Biotechnology Progress. 32 (5): 1103–1112. doi:10.1002/btpr.2327. ISSN 1520-6033. PMID 27452958.

- ^ Xu Y, Wang D, Mason B, Rossomando T, Li N, Liu D, et al. (17 December 2018). "Structure, heterogeneity and developability assessment of therapeutic antibodies". mAbs. 11 (2): 239–264. doi:10.1080/19420862.2018.1553476. ISSN 1942-0862. PMC 6380400. PMID 30543482.

- ^ Beck A, Nowak C, Meshulam D, Reynolds K, Chen D, Pacardo DB, et al. (20 November 2022). "Risk-Based Control Strategies of Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody Charge Variants". Antibodies. 11 (4): 73. doi:10.3390/antib11040073. ISSN 2073-4468. PMC 9703962. PMID 36412839.

- ^ Beck A, Wurch T, Bailly C, Corvaia N (May 2010). "Strategies and challenges for the next generation of therapeutic antibodies". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 10 (5): 345–352. doi:10.1038/nri2747. PMID 20414207. S2CID 29689097.

- ^ Khawli LA, Goswami S, Hutchinson R, Kwong ZW, Yang J, Wang X, et al. (2010). "Charge variants in IgG1: Isolation, characterization, in vitro binding properties and pharmacokinetics in rats". mAbs. 2 (6): 613–624. doi:10.4161/mabs.2.6.13333. PMC 3011216. PMID 20818176.

- ^ Zhang T, Bourret J, Cano T (August 2011). "Isolation and characterization of therapeutic antibody charge variants using cation exchange displacement chromatography". Journal of Chromatography A. 1218 (31): 5079–5086. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.061. PMID 21700290.

- ^ Rathore AS, Winkle H (January 2009). "Quality by design for biopharmaceuticals". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1038/nbt0109-26. PMID 19131992. S2CID 5523554.

- ^ van der Schoot JM, Fennemann FL, Valente M, Dolen Y, Hagemans IM, Becker AM, et al. (August 2019). "Functional diversification of hybridoma-produced antibodies by CRISPR/HDR genomic engineering". Science Advances. 5 (8): eaaw1822. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.1822V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw1822. PMC 6713500. PMID 31489367.

- ^ Siegel DL (January 2002). "Recombinant monoclonal antibody technology". Transfusion Clinique et Biologique. 9 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1016/S1246-7820(01)00210-5. PMID 11889896.

- ^ "Dr. George Pieczenik". LMB Alumni. MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB). 17 September 2009. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Schmitz U, Versmold A, Kaufmann P, Frank HG (2000). "Phage display: a molecular tool for the generation of antibodies – a review". Placenta. 21 (Suppl A): S106 – S112. doi:10.1053/plac.1999.0511. PMID 10831134.

- ^ Zhang YF, Ho M (September 2016). "Humanization of high-affinity antibodies targeting glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma". Scientific Reports. 6: 33878. Bibcode:2016NatSR...633878Z. doi:10.1038/srep33878. PMC 5036187. PMID 27667400.

- ^ Boulianne GL, Hozumi N, Shulman MJ (1984). "Production of functional chimaeric mouse/human antibody". Nature. 312 (5995): 643–646. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..643B. doi:10.1038/312643a0. PMID 6095115. S2CID 4311503.

- ^ Chadd HE, Chamow SM (April 2001). "Therapeutic antibody expression technology". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 12 (2): 188–194. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00198-1. PMID 11287236.

- ^ Lonberg N, Huszar D (1995). "Human antibodies from transgenic mice". International Reviews of Immunology. 13 (1): 65–93. doi:10.3109/08830189509061738. PMID 7494109.

- ^ Hernandez I, Bott SW, Patel AS, Wolf CG, Hospodar AR, Sampathkumar S, et al. (February 2018). "Pricing of monoclonal antibody therapies: higher if used for cancer?". The American Journal of Managed Care. 24 (2): 109–112. PMID 29461857.

- ^ Breedveld FC (February 2000). "Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies". Lancet. 355 (9205): 735–740. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)01034-5. PMID 10703815. S2CID 43781004.

- ^ Australian Prescriber (2006). "Monoclonal antibody therapy for non-malignant disease". Australian Prescriber. 29 (5): 130–133. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2006.079. Archived from the original on 3 November 2006.

- ^ Rosenn (September 2023). "Monoclonal War: The Antibody Arsenal and Targets for Expanded Application". Immuno. 3 (3): 346-357. doi:10.3390/immuno3030021.

- ^ Modified from Carter P (November 2001). "Improving the efficacy of antibody-based cancer therapies". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 1 (2): 118–129. doi:10.1038/35101072. PMID 11905803. S2CID 10169378.

- ^ Takimoto CH, Calvo E. (1 January 2005) "Principles of Oncologic Pharmacotherapy" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 241, for the examples infliximab, basiliximab, abciximab, daclizumab, palivusamab, gemtuzumab, alemtuzumab and rituximab, and mechanism and mode. ISBN 978-0443071454.

- ^ a b "Bavituximab - Avid Bioservices". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 9 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Emergency Use Authorization letter" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 December 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Bernstein L (14 September 2021). "Biden administration moves to stave off shortages of monoclonal antibodies". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Kozlov M (December 2021). "Omicron overpowers key COVID antibody treatments in early tests". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03829-0. PMID 34937889. S2CID 245442677.

- ^ Kreuzberger N, Hirsch C, Chai KL, Tomlinson E, Khosravi Z, Popp M, et al. (September 2021). "SARS-CoV-2-neutralising monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (9): CD013825. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013825.pub2. PMC 8411904. PMID 34473343.

- ^ a b Hirsch C, Park YS, Piechotta V, Chai KL, Estcourt LJ, Monsef I, et al. (June 2022). "SARS-CoV-2-neutralising monoclonal antibodies to prevent COVID-19". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (6): CD014945. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd014945.pub2. PMC 9205158. PMID 35713300.

- ^ MacMillan C (5 April 2024). "FDA Authorizes COVID Drug Pemgarda for High-Risk Patients". Yale Medicine. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Cavazzoni P (3 April 2024). "EUA 122 Invivyd Pemgarda LOA". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Monoclonal antibodies to treat cancer". American Cancer Society. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Monoclonal antibody drugs for cancer: How they work". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ a b Ogbru O (12 October 2022). Davis CP (ed.). "Monoclonal Antibodies: List, Types, Side Effects & FDA Uses (Cancer)". MedicineNet. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Rajewsky K (November 2019). "The advent and rise of monoclonal antibodies". Nature. 575 (7781): 47–49. Bibcode:2019Natur.575...47R. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02840-w. PMID 31686050.

- Kimball JA. "Monoclonal Antibodies". Kimball's Biology Pages.

External links

[edit]- Monoclonal+antibodies at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Antibodypedia, open-access virtual repository publishing data and commentary on any antibodies available to the scientific community.

- Antibody Purification Handbook Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 604: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).